SUBJECTS

GRADE

Show Results

White Mesa Community Basket Weaving

Lesson Summary

- Rehearse and perform an in-class play.

- Learn about modern Ute basket-weaving.

- Create physical depictions of personal values.

Lesson Plan and Procedure

Lesson Key Facts

- Grade(s): 3, 4, 5, 6

- Subject(s): Drama, English Language Arts, Social Studies, Native American, Tribe Approved

- Duration of lesson: 11+ hours towards a performance

- Author(s): Spencer Duncan

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe selected this lesson content in answer to the question, “What would you like the students of Utah to know about you?” Griselda Rogers, the Ute Mountain Ute Education Director, and Amanda May, White Mesa basket weaver, represented the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe in crafting the lesson to provide expertise, accuracy, and authenticity. The lesson was then approved by the Ute Mountain Ute’s Tribal Council.

Before teaching this lesson, please explain to your students that while there are many Native tribes in the United States, this lesson specifically focuses on experiences of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and does not represent other Indigenous groups, unless specifically identified. We hope other Native tribes will honor their decision to share this part of their history with the students of Utah

Play Script: White Mesa Basketweaving: Amy's First Basket

Welcome to the Play!

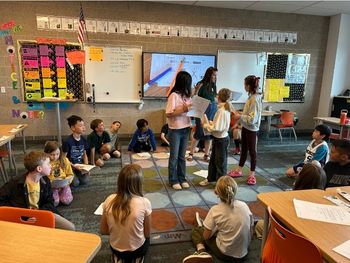

A play is a fun way to learn. When students act, they kinesthetically and verbally connect to language arts and social studies. Often these internal connections stay with them for years and decades to come. But big pay-off comes with a big commitment!

If you’ve never done a class play before, it will take some time! Every class is different, but professionals usually advise you plan one hour of rehearsal for every page in your script. Some pages will take more or less time, but you should plan at least 11 hours to prepare for Amy’s First Basket. Many teachers find they can use language arts time to rehearse if they don’t have a designated arts schedule. If this is too much of a time commitment, a class read through is another excellent way to explore a script.

Suggested Rehearsal Structure

Read-through

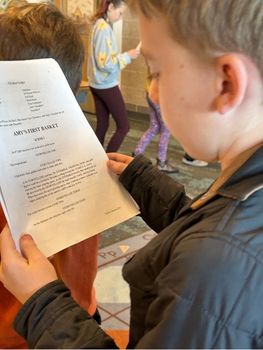

A read-through is where you, the director, and the actors read through the script. Some directors like to first read the entire script to the actors while they follow along, then have the actors verbally read through the script.

When the actors do their read-through, the stage manager (likely you) reads all the stage directions. It is introduced which actor is reading for which character, but character names before lines are not read aloud by anyone. This interrupts the flow of the story and limits actors’ abilities to listen and respond to one another.

Casting

How you cast is up to you. After an initial director’s read-through, you might have students write their names on a white board under the characters they are interested in portraying. Then, in a private space, after class, draw sticks to see who will play what. Everyone who is not a main or supporting character joins the ensemble. If there is a certain student you know who would benefit the most in a role, your hand can be “magnetized” to their stick—ensuring they get the part.

You will know your students’ needs and abilities, although hearing some students read their interested parts before drawing sticks may alert you to “diamonds in the rough.” Often the shy, quiet child or the class comedian gain confidence and focus when motivated by a part they desire. Many professional actors note that they were these types of children; they should not be underestimated.

Once students are cast, have them highlight their parts.

- Rehearsal

Before or in between rehearsals, complete the recommended additional learning activities with your students. Research is essential to a production. Learning about the characters, settings, and staging techniques will not only work towards core standards—it will enrich the quality and depth of your production!

When you give students notes, the limit is three per student: two compliments, one tip for improvement. Any more than this, and you may find actors don’t remember what you’ve said. You might remember a time you experienced too much feedback in one sitting—especially if it was negative! It probably wasn’t very helpful!

- Dress Rehearsal

For in-class productions, unless absolutely necessary, costumes and props should be saved for the last one to three rehearsals. Student actors tend to obsess about them over their lines and lose focus. When you are ready for your last dress rehearsal, invite some other teachers or a class to watch the show. If there were sloppy areas to your production, you’ll usually find a small audience gets kids to clean up their act. (However, if you introduce an audience too early, it may embarrass or distract kids, limiting their creativity!)

- Performance

This is when your students really get to shine! Performing for families, peers, or the community at large raises the stakes. It shows your schoolwork is serious business with real results! Students are bound to get nervous. Have them circle up and give them a good pep talk before the show. Leading students in collective tongue twisters, guided meditation journeys, or counting games can ease nerves, build teamwork, and increase focus—there are plenty of resources online!

- Audience Talk-back

This is a fun and very educational aspect of a play that is often overlooked. After the show and bows, have your students sit on the performing space. With you facilitating the conversation, allow the audience to ask questions of you and your students. What did they learn throughout the rehearsal process? What were their favorite parts? Why did they and you make the decisions you did? Audiences may also be invited to give compliments. You will find evidence for learning emerge and often what the production meant to its participants: both actor and audience.

Recommended Additional Learning Activities

Fact and Fiction

Amy’s First Basket is a work of contemporary historical fiction, inspired by the life and work of artist Amanda May. The White Mesa Community of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the play’s setting of Allen Canyon, and the basket weaving processes included in the script are all real. The conversations and events in the play are fictional, but Amanda, like the character Amy, did find sumac willows in her youth and taught herself to weave: a traditional artform she witnessed her grandmother doing. It is vital students understand they are representing a real-world people who exist and live today in Utah. They and the land of their ancestors have not disappeared.

Introduce students to the real Amanda May, who the script is written about.

Upload Slides: Amanda May, White Mesa Weaver

Slide 1: Amanda May, bio

Slide 2: Preparing a basket

Slide 3: Making a basket, samples

Show your students Amanda May’s picture and read them her artist’s bio.

Together, research pictures of White Mesa and Allen Canyon, the flora and fauna in this script, and maps of tribal lands. You may even wish to look up the White Mesa Community’s government offices and reach out to tribal leaders.

Current contact information may be found at the following:

https://indian.utah.gov/ute-mountain-ute/ https://www.utemountainutetribe.com/white%20mesa%20administration.html

Basic Information on the White Mesa Community can be found in the Utah American Indian Digital Archive: https://utahindians.org/archives/whiteMesa.html

When your students perform this play, it is important to dress appropriately, as noted in the script. If your students are confused why they are wearing familiar, contemporary clothing, help them understand the difference between everyday clothing and Native regalia. Native regalia differs across communities and tribes. To show respect, we do not wear regalia or regalia-inspired costumes unless we have permission.

Do they, the students, have clothing they only wear on very special occasions?

What can people do to show respect to them, the students? What are other ways they can show respect to others, both near and far?

Prepare your student actors with drama warm-up activities, and character development skills, like the following:

The Martha Game

This is a good precursor to tableaux work, which features prominently in the script.

One student goes to the front of the room. They announce what they are: “I’m a coconut tree!” They then freeze like their object.

Another student joins them as something that could harmonize with the established scene: “I’m a monkey!”

Then another (“I’m a coconut that fell on the ground!”) and another (“I’m the monkey’s mother!”) and another (“I’m a snake that eats monkeys!”) until all the students are frozen into one uniform picture.

If students need it, you can write a setting or prompt on the board to establish each round of the game.

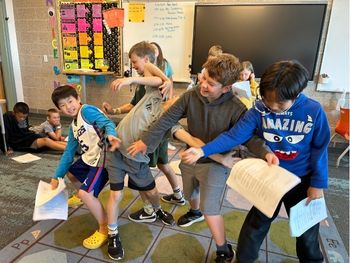

Tableaux

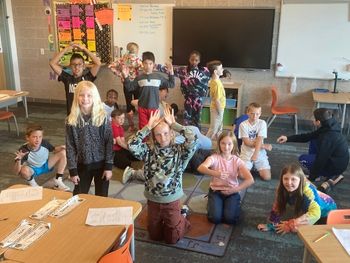

Tableaux are frozen pictures that tell a story. Hundreds of years ago, before television and movies, people would create tableaux with their bodies to pass the time. In the play Amy’s First Basket, actors create tableaux to show what matters to them.

As a class, write a list of prompts on the board (e.g. “Aunt Judy’s Birthday Party,” “Ocean Adventure,” “The Dirtiest Bedroom in the World,” “Alien Invasion,“ “Our School”)

Divide the students into groups. Each group has a director (and perhaps an assistant director, should you need it). You are the producer.

You, the producer, calls out one of the prompts. The groups have 60 seconds to arrange themselves in a scene depicting that prompt, just like they practiced in the Martha Game. When time is up, everyone must freeze.

The director then has an additional 60 seconds to adjust the positions of the actors to make the image more aesthetically pleasing or interesting (levels, spacing, shapes, facial reactions). They may only touch the actors’ hands and shoulders. For every other change, they must verbally coach the actors.

Once students have the hang of creating tableaux, you can have the director join the actors. The students will now create a beginning, middle, and end image for each prompt.

Call out a prompt, widen your hands, and slowly count down from three. “Alien Invasion in three, two, one! Beginning!” When you reach beginning, middle, or end, the students must freeze. It is okay if they don’t know the story; they are improvising it.

Next do the middle image, then the end image. Take pictures with a real or imaginary cameras—students may love seeing their creative tableaux!

Repeat all three images at least two more times with each prompt, getting faster in your countdowns. This will let students feel they can improve their images. It will also get them better at working quickly together.

Character Analysis

Actors always do a character analysis. These can be quite complex, but here is an idea for a simplified version:

Have your students write their character’s name and draw how they imagine their character look. On the back, have them answer any of the following six questions:

- What does your character want the most? (This is their character’s objective.)

- Why do they want that thing? (This is their character’s motive.)

- How do they get what they want? (These are their character’s tactics.)

- Do they have any secrets? (All characters have secrets.)

- What are three other things you know about your character?

- What would you like to ask your character?

Main characters will find clues to their answers in the script. Ensemble characters have a greater ability to imagine their own answers. Both types of characters should use contextual clues to fill in what isn’t spelled out!

Learning Objectives

- Foster a deeper understanding of Ute Mountain Ute culture.

- Interpret and memorize a script.

- Understand the significance of Native American basket weaving.

- Create and represent a character in a performance.

- Develop physical representations of personal values.

Utah State Board of Education Standards

This lesson can be used to meet standards in many grades and subject areas. We will highlight one grade’s standards to give an example of application.

4th Grade Social Studies

- Standard 4.5.6: Choose one of Utah’s cultural institutions and explain its historical significance as well as the cultural benefits to Utah families and our nation.

4th Grade Fine Arts - Drama

- Standard 4.T.CR.5: Create character through imagination, physical movement, gesture, sound and/or speech and facial expression.

- Standard 4.T.CR.7: Recognize that participating in the rehearsal process is necessary to refine and revise

- Standard 4.T.P.4: Communicate meaning using the body through space, shape, energy and gesture.

- Standard 4.T.P.9: Perform a variety of dramatic works for peers or invited audiences.

4th Grade Language Arts

- Standard 4.R.12: Compare a visual or oral presentation of a story or drama with the text itself and identify where each version reflects specific descriptions and directions in the text. (RL)

- Standard 4.SL.3: Use age-appropriate language, grammar, volume, and clear pronunciation when speaking or presenting.

Equipment and Materials Needed

Additional Resources

This lesson is supported by the National Endowment of the Arts and the Utah Division of Arts & Museums

Basket-Weaving Links and Videos

Baskets are a cultural part of many tribes. Some baskets are woven with sumac, like the ones in our play. Others are woven with yucca. You or your students may find it useful to watch clips from the following videos to gain a better understanding of Native American basket-weaving at large.

As you watch, ask yourself: what similarities do I see to the Ute Mountain Ute basket weaving process depicted in our play? What differences do I notice?

- Contemporary Navajo Baskets (many weaved by White Mesa Residents):

https://issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume74_2006_number3/s/10311056 - Twin Rocks Trading Post Baskets (where many White Mesa Baskets are sold):

https://twinrocks.com/baskets.html - Navajo/Diné Sumac Splitting Technique:

https://youtu.be/_ok3vfy6uYw?si=ovzkZvKwLoVnJpS6 - Navajo/Diné Sumac Lacing Technique:

https://youtu.be/f3t1rDXkYSE?si=UwoipTPaS08obgwU - Navajo Ceremonial Basket by Mary Holiday Black:

https://youtu.be/fj_VPAAv42g?si=-AWPjFnTAabkJWqH - Navajo Wedding Basket Symbolism and Use:

https://youtu.be/_8-cBhjNCyo?si=DAJusZtASTXeZ3Pq - Apache Burden Basket Weaving:

https://youtu.be/_2IMD7rKblA?si=Hoi0XBRxi3T60Q2g - Tohono O’odhom Weaving:

https://youtu.be/G2iM9_wFe0s?si=_L_LYcQFO2Msr9mH - California Basket Weavers Association’s “The Art of Basket Weaving”:

https://youtu.be/DAm1OaW84pM?si=hfakIL4pko_jTS3T

Image References

Amanda May images taken by Emily Soderborg in White Mesa Community

www.education.byu.edu/arts/lessons

Download

Download