SUBJECTS

GRADE

Show Results

Iron Horses

Lesson Summary

- Explore the basic locomotor movement of galloping.

- Read the book Iron Horses.

- Work in groups to create original movement inspired by the book.

- Perform, reflect, and connect.

Lesson Plan and Procedure

Lesson Key Facts

- Grade(s): 4, 5, 6

- Subject(s): Dance, English Language Arts, Health, Social Studies

- Duration of lesson: 60 minutes

- Author(s): Miriam Bowen

Note: This lesson is one of a group of lessons created to teach about the Transcontinental Railroad through the arts. Titles of the lessons can be found in the additional resources section below.

Preparation

- Buy two copies of the book Iron Horses. Carefully cut the pages from one copy and laminate them for durability during student use. They work best when paired together, as shown in the book.

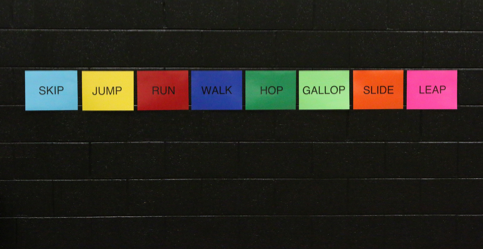

- Make word strips to display the eight basic locomotor movements (as shown below in figure 1).

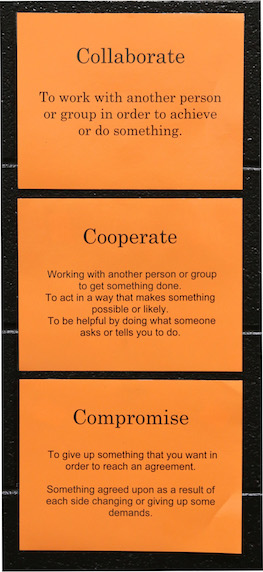

- Make word strips for the group work section, then collaborate, cooperate, and compromise (as shown in figure 2).

- Print the group-work assessment sheet (see equipment and materials section), one copy for each group.

Activity 1: Warming Up

Write the word locomotor on the board. Ask the students to find the word motor within the word. You could ask what things have motors in them.

Teacher: Locomotor movement refers to body movements that move the body from one place to another or cause the body to travel. Locomotor movements are the foundations of human movement. The eight basic locomotor movements are walking, running, hopping, skipping, jumping, galloping, leaping, and sliding. (Display the words on a board or wall.)

Teacher: Let’s begin with walking. As I tap my drum, begin walking through the room. Make sure to keep space around you so you don’t bump into anyone or anything. (Keep a steady walking beat on your drum as the students walk.)

To add interest, or as time permits, encourage speed changes such as fast and slow, directional changes such as backward and sideways, and pathways such as straight, curved, and zig-zag.

After exploring this movement, tell your students that at an average pace, a person walks approximately 3.1 miles per hour.

Teacher: If walking was your only form of transportation, would it take long to travel to school or other locations? Would your body need rest and food along the way? Would you want to find a faster way of travel?

Teacher: A gallop is the fastest pace a horse can run, with all its feet off the ground. (Show images of horses galloping, and have students notice the height in the horse’s knees.)

Teacher: Let’s try this locomotor movement, galloping. (Encourage the students to lift their knees high as they gallop. You may continue beating a hand drum or use music suggested in the additional resources section.)

If your space is small and your group is large, you can divide the group in half and have them take turns watching and galloping.

Note: If you divide them, this is the perfect opportunity to establish performance etiquette, which includes the following:

- Focus on the performers, noticing what they do.

- Cross legs and hold still while watching.

- Don’t talk during the performance.

- Clap at the conclusion to show appreciation and respect for the performers.

After a vigorous minute or so of galloping, invite your students to sit down.

Teacher: Were you able to travel faster with your walk or gallop? Which took more energy?

Teacher: Were you able to travel faster with your walk or gallop? Which took more energy?

Your students should recognize that the gallop took more energy than the walk did. They will be ready for rest. Direct them to breathe in deeply through their noses and out through their mouths to find recovery.

Teacher: Can you imagine some of the traveling challenges people faced before the forms of transportation we have today were invented? Did you know that horses travel 10 to 15 miles per hour, depending on their strength and energy? Compare that to the 3.1 miles per hour of a walking human.

Activity 2: Iron Horses

Read the entire book Iron Horses by Verla Kay, including the author’s note on the last page. Take time to define words and play with movement ideas that the descriptive words inspire. This will be a model, preparing students for the next activity. Make connections between people walking, horses galloping, and the Transcontinental Railroad. Point out the speed of travel from Missouri to California going from six months to six days with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

Discussion suggestions:

- Why do you think the author titled the book Iron Horses?

- What were the different forms of transportation in the early 1800s?

- What was the reason for needing a railroad?

- How did the railroad impact our nation?

- What do you think a day was like for those working on the railroad?

- Did the railroad have an impact on the people living in its path?

- What were the motives? (Locomotive.) How did different groups of people perceive the railroad?

- What were the national ideas about the railroad versus the reality of what really happened?

- Can you make any connections with this event in history to our lives now?

Activity 3

Number the students one through six, depending on the size of your group. Have them gather in their designated groups and establish expectations.

Teacher: It is important to collaborate, cooperate, and sometimes compromise when working in a group. (Display these words in some form for the students to see.)

Explain that we can know we are working well together when we do the following:

- Show respect for others.

- Work hard the whole time.

- Push ourselves to contribute and try new things.

- Use our creativity and imagination.

- Work to create something wonderful to add to the dance.

Give each group a copy of the group-work assessment sheet (see equipment and materials section) as a guide while working together. Allow one or two groups at a time to choose a couple of pages you have prepared from your cut and laminated book Iron Horses (two two-page layouts).

Teacher: Read the text on the pages you have chosen, and carefully observe the artwork of Michael McCurdy to understand what is being communicated. Work together to create movement that can show the meaning and intent of that page. (If there are extra pages not chosen, set them to the side; they can just be read through.)

Groups with questions may raise their hands to indicate a need for assistance. Set aside time for creating and choreographing. Encourage groups to move more than talk; once decisions are made, have students practice the sequence.

Performance

Have the class gather in a large circle and sit down next to the members of their group. Explain that as you open the book for a second reading, the groups need to look and listen for the pages they have chosen. They will move into the middle of the circle to perform their movement sequence as their chosen page is read. They will then return to their spots to watch and listen until their next page is to be read. Read the book again from beginning to end.

Option: You could ask your students to say the text from the pages they chose. They could do this in unison while moving or select one person in the group to be the narrator.

Option: You could ask your students to say the text from the pages they chose. They could do this in unison while moving or select one person in the group to be the narrator.

Establish or review performance etiquette.

Teacher: If this was a comedy, we would encourage laughter, but since it is our best work, no laughter will be allowed from performers or audience members.

Note: If there is laughter, stop and remind your students of the safe space you have created for sharing movement ideas. When they are ready, pick up where you left off. This is an important part that you as the teacher play in the success of your class experience.

When the performance is finished, allow time for the students to clap, showing appreciation and respect for the class production. Take this opportunity as the teacher to highlight the excellent work and efforts you observed in your students. Have a class discussion, encouraging students to make connections and reflect on what they have learned and accomplished.

Discussion seed ideas:

- What was your favorite part of today?

- Have you learned something new? What?

- Did you notice how the movements chosen reflected the intent of the author and illustrator?

- What have you thought about today that you have not thought of before?

- Did you most enjoy being a performer or an audience member?

- Why is it important for us to know about this historical event in Utah?

- How did the railroad make life better for our country?

- Do you think there were problems as the railroad was built? Explain.

- Do you think there were dangers and sacrifices in this process? Explain.

- Did everyone think and feel the same way about this westward expansion?

- Do you want to learn more about the Transcontinental Railroad?

- What can you do to move forward in your life’s journey, making wiser decisions than those which were made in the past?

- How will you use what you learned today to help you move forward in positive ways?

Learning Objectives

- Understand and explore locomotor movement.

- Create original movement from details in text and illustrations that express intent.

- Use performance etiquette.

- Form healthy interpersonal relationships.

- Communicate ideas about a historical period.

Utah State Board of Education Standards

This lesson can be used to meet standards in many grades and subject areas. We will highlight one grade's standards to give an example of application.

Grade 5 Dance

- Standard 5.D.CR.1: Demonstrate willingness to try new ideas, methods, and approaches when creating dance.

- Standard 5.D.CR.3: Develop a dance study, creating original movement that expresses and communicates a main idea.

- Standard 5.D.P.4: Recall and execute a series of dance phrases using fundamental dance skills.

- Standard 5.D.P.9: Use performance etiquette and practices during class, rehearsal, and in formal and informal performance spaces.

Grade 5 Social Studies

Standard 5.4.1: Use evidence from multiple perspectives (for example, pioneers, 49ers, Black Americans, Chinese Americans, Native Americans, new immigrants, people experiencing religious persecution) to make a case for the most significant social, economic, and environmental changes brought about by Westward Expansion and the Industrial Revolution.

Standard 5.4.2: Use primary sources to explain the driving forces for why people immigrated and emigrated during the 19th century, as well as the ways that movement changed the nation.

Grade 5 English Language Arts

- Standard 5.R.6: Determine the theme or main idea of a text including those from diverse cultures and how it is conveyed through particular details and summarize the text. (RL & RI)

- Standard 5.R.8: Determine the meaning of words, phrases, figurative language, academic and content-specific words, and analyze their effect on meaning within a text. (RL & RI)

Grade 5 Health

- Standard 5.HF.4: Demonstrate ways to express gratitude and treat others with dignity and respect.

Equipment and Materials Needed

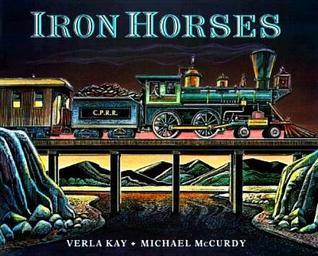

- Two copies of the following book: Kay, Verla, and Michael McCurdy. Iron Horses. New York: Putnam, 1999.

- Hand drum and mallet

- Music

- Word strips to display the eight basic locomotor movements PDF

- Word strips for the group work section PDF

- Copies of the group-work assessment for each group PDF

Additional Resources

- This is one of several lessons created to teach about the Transcontinental Railroad. The other lessons in the unit include the following:

- "Transcontinental Railroad— David Dynak” PDF

- “The Lost Souls of the Transcontinental Railroad”

- “Transcontinental Railroad and the American West: Making Tracks”

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Promontory,_Utah

- https://americanhistory.si.edu/america-on-the-move/transportation-1876

- Galloping music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ktIAD_OWM-8

- Galloping music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-t3fBEEnQuM

- Train music by Zoe Keating: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8x98xVl6c6k

- Train music by Tangerine Dream: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M00m_u8-0Yk

Image References

Image 1: James Huston.

Image 2: Miriam Bowen.

Image 3: www.shutterstock.com

Image 4: James Huston.

Image 5: www.alibris.com

Image 6–11: James Huston.

www.education.byu.edu/arts/lessons

Download

Download