After perusing the more than 2,000 figurines in Dr. Pam Mayes' office, Mayes' morbidly obese client keyed in on a very delicate and gorgeous fairy sitting on a leaf. The woman placed the fairy in her sand tray. One by one, the woman positioned each subsequent figurine facing the fairy. Girls often use fairies in sand tray therapy, so when this adult woman chose the fairy, Mayes suspected that her client felt a tremendous amount of sadness and loss stemming from her adolescence.

"I asked her what would happen if she took a mature woman figurine she had put in the tray and turned it around so it was facing her," Pam said. "She did that, and you could see her whole face change. She said, 'Oh my goodness.' It was both an emotional and a perceptual change for her -- the idea that she didn't have to keep focusing on that fairy character."

Dr. Cliff Mayes, professor in the Department of Educational Leadership and Foundations within the McKay School of Education, and his wife, Dr. Pam Mayes, were both trained in Jungian psychology. The early 20th century founder of analytical psychology, Carl Jung introduced a multitude of depth psychology's earliest concepts and clinical techniques. A lasting mark of Jung's body of work came at the hands of one of his pupils, Dora Kalff, who in the 1920s and '30s developed sand tray therapy.

Sand tray therapy is a method in which clients with a variety of psychological issues place figurines in a four-foot by three-foot tray full of sand. The tray, which is no wider than one's straight forward field of vision, allows patients to focus on telling a story with their chosen figurines -- just as children play in a sandbox. "The idea is you create and sort of disappear into a world," says Pam. "Sand tends to ground you, make you more in touch with your body and make your more in touch with being a child. You're working with symbols rather than working with concepts, so you naturally move toward deeper levels of awareness. It's almost like accessing a dream."

The revelations patients derive from these "dreams" are what drive the Mayes in this procedure. "We're pretty radical in the way we approach things," says Cliff. "In classical sand tray analysis, the therapist is really not supposed to say much at all. It's a process that you just sort of observe. We're a lot more active."

Cliff explains that he and his wife talk with their clients during and after their sand tray stories. "We don't tell them what to do, but sometimes we ask them how they would feel if things were arranged in a different way," he said. "What that does," Pam continued, "is it accesses a soul-level at which people will open up." It's at these levels where clients see the stories they've made in the sand, and then make connections to how their stories relate to reality. "Brain surgeons put electrodes on the patients' brains to listen for things," Pam says. "Sand tray therapy is very much like that in a sense. The effect is that you're helping clients move into their own profound depths."

The Mayes say clients are never completely surprised by what they've uncovered about themselves in sand tray therapy. "We do very little interpreting for them," Pam says, "although we do a great deal of it with them. Once their story is there in front of them, they realize 'Oh yeah, that really is what's going on.'"

Sand tray therapy originally began as way to help children articulate their feelings. But in the years since, its use has been extended to adults. This summer, The International Journal of Play Therapy will highlight the Mayes' revolutionary work with an article entitled, "Sand Tray Therapy with a 24-year-old Woman in the Residual Phase of Schizophrenia." The article will feature the Mayes' work with this particular client as well as bring to light, what has been called in the sand tray literature, the Mayes Hypothesis -- a theory the couple has developed on how to read sand trays.

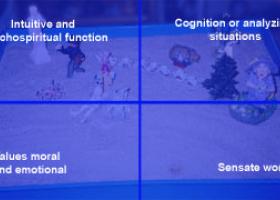

"We believe that different quadrants of the sand tray tend to embody different issues," Cliff says. In the lower-right quadrant, the Mayes see issues relating to the person's sensate world. "How the person processes the world in terms of physical issues," Cliff says. The upper-right quadrant represents issues that are more related to strict cognition or analyzing situations. The upper-left is the intuitive and psychospiritual function, while the lower-left quadrant symbolizes how people value things and relationships morally and emotionally.

The Mayes' forthcoming publication details their work with a woman during the least volatile stages of schizophrenia, when her symptoms became manageable. She has a poor relationship with her father, who is also schizophrenic. As a result, Cliff and Pam decided to have Cliff do the sand tray therapy in an effort to cultivate a positive transference between the client and an older, facilitating male. Transference is when a client projects certain feelings on their therapist. "In a lot of the literature, the sand tray therapist is characterized almost entirely in maternal terms -- as what the Jungian theorist Erich Neumann called the Great Archetypal Mother," Pam says. "[With Cliff,] the client was able to see him as a good father figure, so there were issues about her father that came up that she could talk about with him."

Sand tray therapy gave this client a chance to express herself in new ways. "She did something that I've never seen before in sand tray therapy," Pam says. "She would stack figurines on top of each other as if that's how she is experiencing life -- a split between mind and body. If we had done a talk therapy with her," Pam explained, "we'd have been dealing with the voices that are speaking to her. It would have all been focused on her manifestations of schizophrenia. But, when she got a chance to put figures in the sand, then it's almost like she got into just being a person, not being a schizophrenic."

The Mayes' more than yearlong involvement with the woman, who is now pursuing a master's degree, helped her deal with vocational, physical, social and familial issues she had been struggling with for many years. "She now has a much more open relationship with her sister," Cliff says. "Her relationship with her mother became more mature and more authentic. We were able to deal with her fear of men."

"I'm not sure she would have begun to resolve those issues without sand tray therapy," Cliff added. "Medication helps with explicit symptoms such as hearing voices, hallucinations or experiencing speech disorders. But medication doesn't get to deep psychodynamic issues. Sand tray therapy does."

Sand tray therapy is not just for people with psychological problems. The Mayes have used sand tray therapy in working with couples, and Cliff has even used it with graduate students here at the McKay School. Although, in this case it's not "therapy," Cliff has had students at the beginning of the cohort year do a sand tray about their vision of themselves as educational leaders.

"We have them do it at the end of the year as well, and we've noted some really interesting changes that have occurred," Cliff says. "For instance, when students came into the cohort in our program, if they experienced some anxiety about the heavy theoretical component that there is in our program, you'd often see various conflicts expressed in the upper-right quadrant [strict cognition] -- or nothing at all as if to avoid those issues."

He says the students like doing sand trays because it's a way for them to reflect on why they have chosen to become teachers and educational leaders. "They tell a story, and they see how the story is revealing all these things about themselves and to themselves as school people," Cliff says. "Then they compare it to the sand tray they do at the end of the program, and they see how they've evolved. It's been a pretty powerful tool for them both to see change and to create change in their vision of themselves as school people and in their professional practice."